Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one. A.J. Liebling minted [4] that axiom in the New Yorker magazine in 1960. Later that decade, researchers began work on creating packet-switching networks [5], and a U.S. government project created a network of networks called ARPANET [6], the forerunner to the Internet. And with the rise of the Internet came the fall of that axiom. Today news [7] organizations [8], as well as individual [9] persons [10], can freely publish, without an expensive printing press, to a wide audience.

All bits are created equal. That axiom sums up the rule of net neutrality [11] — that the Internet moves data packets from end to end, blind to their content, and without bias to their origin and destination. That equality came naturally from the plain old telephone system that most persons once used to get on the Internet. Like the telegraph system that came before it, a telephone system is deemed a "common carrier," [12] a public delivery service that treats all cargo — phone call communications in this case — equally. By law, the telephone company could not interfere with a phone call, whether dialing Mom or dialing-up one’s ISP [13]. The system heeded the rule of net neutrality, which gave us the open playing field [14] for uncensored and inexpensive publishing, and the rapid rise of the Internet to become one of the greatest achievements of humankind.

The price of freedom is eternal vigilance. Today, freedom of press and speech is threatened by the big telecommunications companies. No longer do most persons pick from one of many ISP’s to dial-up. Now they must use the only available ISP — the telecom that owns their DSL, cable or cellular network. And no longer are those telecoms classified "telecommunication services," which are common carriers. During the Bush II administration, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) instead classified those telecoms [12] as "information services," which are not common carriers. The FCC at that time also issued openness principles [15] that tend towards net neutrality. But in 2010 a federal court, in a case brought by Comcast [16], ruled against the FCC enforcing those principles for an "information service." So the FCC turned those principles into its Open Internet Order [17]. But just this year a federal court, in Verizon vs. FCC [18]," ruled against the FCC enforcing that order for an "information service." In court, Verizon claimed [19] that it had "editorial discretion" over data that travels on its lines. With that claim, and with the known [20] cases [21] of big telecoms fiddling with data flow, we can foresee a rollback of press freedom, and the rise of an axiom like the old one — "Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own an Internet gateway."

Where there’s a will, there’s a way. That timeless axiom often runs up against another old one — "Money talks." Right after the "Verizon vs. FCC" ruling, press and Internet freedom organizations began a campaign to reclassify the telecoms as common carriers. And two weeks later, they delivered a petition [22] with a million signatures urging that to the FCC. But Michael Powell, who headed the FCC when it first freed big telecoms from common carrier responsibilities, and is now the head lobbyist for the telecoms, warned that such an act [23] by the FCC would bring "World War III." And so the battle line is drawn: on one side the will of the masses of Internet users and news organizations, and on the other the big money of a few mega-corporations. So far, Chairman Tom Wheeler has said [24] the FCC will not reclassify, and will pursue new [25] (most likely weaker) rules. And while some Democrats favor [26] making net neutrality the law of the land, such a bill would face a stonewall [27] of virtually all Republicans.

If you want something done right, do it yourself. But the fight for press and Internet freedom goes beyond the FCC and Congress. One way to get around big telecom high prices, low speeds [28], and their plans to control [29] the Internet, is to have your local government build [30] its own network. Such publicly owned networks [31] and ISP’s now operate in cities such as Chattanooga; Bristol, Virginia; and Lafayette, Louisiana. Each of those cities’ systems runs on fiber optic lines, offers 1Gbps speed, and serves residential, as well as business, customers. Those customers get much more speed [32] and reliability for their dollar. And they get a connection with net neutrality — the freedom to read and publish without interference.

Sources

A.J. Liebling minted [4] Wikiquote

packet-switching networks [5] Wikipedia

ARPANET [6] Wikipedia

news [7] Pro Publica

organizations [8] Consortiumnews

individual [9] The Daily Howler by Bob Somerby

persons [10] David Swanson

net neutrality [11] “Network Neutrality FAQ” by Tim Wu, who coined the term “network neutrality” in his paper “Network Neutrality, Broadband Discrimination [33].”

Network neutrality is best defined as a network design principle. The idea is that a maximally useful public information network aspires to treat all content, sites, and platforms equally. This allows the network to carry every form of information and support every kind of application. The principle suggests that information networks are often more valuable when they are less specialized – when they are a platform for multiple uses, present and future. (For people who know more about network design, what is just described is similar to the “end-to-end” design principle).

(Note that this doesn’t suggest every network has to be neutral to be useful. Discriminatory, private networks can be extremely useful for other purposes. What the principle suggests that there is such a thing as a neutral public network, which has a particular value that depends on its neutral nature).

A useful way to understand this principle is to look at other networks, like the electric grid, which are implicitly built on a neutrality theory. The general purpose and neutral nature of the electric grid is one of the things that make it extremely useful. The electric grid does not care if you plug in a toaster, an iron, or a computer. Consequently it has survived and supported giant waves of innovation in the appliance market. The electric grid worked for the radios of the 1930s works for the flat screen TVs of the 2000s. For that reason the electric grid is a model of a neutral, innovation-driving network.

… The internet isn’t perfect but it aspires for neutrality in its original design. Its decentralized and mostly neutral nature may account for its success as an economic engine and a source of folk culture.

deemed a “common carrier,” [12] “Reclassification Is Not a Dirty Word” by Candace Clement and S. Derek Turner; Freepress; January 17, 2014

Since its earliest days, our nation’s communications network has always been treated under the law as a “common carriage” network. This means that it was open to all, and the network owner had to serve all customers without discrimination. Government’s role in all this was to make sure that these networks were accessible to anyone who wanted to use them, for whatever purpose.

Because the phone company could not interfere with the content flowing over the network, some really smart people in the 1960s and early 1970s were able to use it to connect computers together, giving rise to the Internet. Other smart people then came along and used the open network to launch innovations like the World Wide Web, browsers, Instant Messaging, RSS and the almost limitless other things we all use the Internet for everyday.

Because of common carriage these innovators were able to use the network to launch amazing innovations without first asking the phone company for permission. And, it is important to note, that common carriage has nothing to do with whether or not the network owner is a monopolist. Hotels, shippers, airlines, long distance phone companies, cell phone companies and many others operating in non-monopoly markets have all historically been treated as common carriers.

ISP [13] Wikipedia

gave us the open playing field [14] “Nearly 50 Online Journalism Innovators Pledge Support for Net Neutrality” Letter to Chairman Genachowski and members of Congress

We, the undersigned, ask you to stand with us in favor of “Net Neutrality.” Freedom of the press is a central tenant of our democracy and the Internet is today’s printing press. As journalists we understand that Net Neutrality is at its core about people’s access to information. The future of journalism in America depends on an open and free flowing Internet.

classified those telecoms [12] “Reclassification Is Not a Dirty Word” by Candace Clement and S. Derek Turner; Freepress; January 17, 2014

When Congress wrote the 1996 Telecommunication Act, it essentially codified this distinction between “content” and “carriage.” Communications networks that offered two-way connectivity to the general public — be they the traditional wired phone network or the newer wireless and cable systems — were all deemed “telecommunications services,” and the content and applications that rode over these IP-based networks were called “information services.” Telecommunications services were subject to the basic common carrier provisions of Title II of the Communications Act, while information services were left unregulated.

…

In 2002, the FCC made a big misstep. Caving to pressure from the cable industry, the FCC (chaired by current head lobbyist for the cable industry, Michael Powell) decided that if you were getting broadband from a cable modem, it should not be treated with the same common carriage protections. The Powell FCC declared that cable broadband was an “information service”— which meant that these ISPs could block and slow down websites and applications.

This sparked a lengthy legal case, where the FCC’s decision was first overturned by an appeals court, then upheld by the Supreme Court in a split decision. But the court did not state whether the FCC’s move to classify broadband as an “information service” was right or wrong, only that it had a right to reclassify (a right which it retains to this day should it decide to act on this week’s court decision).

In 2005, following the Supreme Court’s decision in the cable modem case, the FCC applied the “information services” classification to broadband offered over all other platforms (including DSL and other phone company broadband technologies, that at the time were treated as common carrier services). This FCC reclassification of broadband from a telecom to an information service removed the common carrier protections that were key to the initial development and rapid growth of the Internet.

openness principles [15] Policy Statement; FCC; September 23, 2005

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to access the lawful Internet content of their choice.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to run applications and use services of their choice, subject to the needs of law enforcement.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to connect their choice of legal devices that do not harm the network.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to competition among network providers, application and service providers, and content providers.

case brought by Comcast [16] “Federal Court Strikes Down the FCC’s ‘Net Neutrality’ Authority” by Sam Gustin; DailyFinance Apr 6th 2010

[T]he court ruled that “The commission has failed to tie its assertion of ancillary authority over Comcast’s Internet service to any statutorily mandated responsibility.”

Open Internet Order [17] “Open Internet Rules & Order” – FCC; November 20, 2011

The FCC has adopted three basic open Internet rules:

- Transparency. Broadband providers must disclose information regarding their network management practices, performance, and the commercial terms of their broadband services.

- No blocking. Fixed broadband providers (such as DSL, cable modem, or fixed wireless providers) may not block lawful content, applications, services, or non-harmful devices. Mobile broadband providers may not block lawful websites, or applications that compete with their voice or video telephony services.

- No unreasonable discrimination. Fixed broadband providers may not unreasonably discriminate in transmitting lawful network traffic over a consumer’s broadband Internet access service. Unreasonable discrimination of network traffic could take the form of particular services or websites appearing slower or degraded in quality.

Verizon vs. FCC [18] “The Net Neutrality Court Case Decoded” – Freepress; January 15, 2014

The court in the Verizon v. FCC [34] case clearly stated that the FCC lacks authority because of “the Commission’s still-binding decision to classify broadband providers not as providers of ‘telecommunications services’ but instead as providers of ‘information services.’ ”

The FCC is free to revisit those prior classification decisions. And if it rightly decides that broadband is what we all know it is — a connection to the outside world that is merely faster than the phone lines we used to use for dial-up access, phone calls and faxes — then it can “reclassify” the transmission component of an ISPs service back under the law as a “telecommunications service.”

Doing so would give the FCC the clear authority to adopt Net Neutrality rules, and/or intervene in the case of an ISP harming the open Internet through discriminatory practices.

What all this means is that the fix for the Open Internet is actually easy: The FCC needs to reverse its prior decisions and “reclassify” Internet access services “telecommunications services” under the law and treat ISPs as the “common carriers” they already are.

Verizon claimed [19] “Censorship = Freedom?” by Timothy Karr; Save the Internet; July 16, 2012

In the brief, Verizon argues that the First Amendment gives the company the right to serve as the Internet’s editor-in-chief.

The First Amendment “protects those transmitting the speech of others, and those who ‘exercise editorial discretion’ in selecting which speech to transmit and how to transmit it,” the company’s attorneys wrote. “In performing these functions, broadband providers possess ‘editorial discretion.’ Just as a newspaper is entitled to decide which content to publish and where, broadband providers may feature some content over others.”

By “content” Verizon means all digital communications that cross its wires, from photographs of your cousin’s backyard barbeque to YouTube videos of human rights violations in Syria.

known [20] “Why the FCC Can’t Actually Save Net Neutrality” By April Glaser; Electronic Frontier Foundation; January 27, 2014

Here are a few ways ISPs have throttled or blocked content in the past …:

- Packet forgery: in 2007 Comcast was caught interfering with their customers’ use of BitTorrent and other peer-to-peer file sharing;

- Discriminatory traffic shaping that prioritizes some protocols over others: a Canadian ISP slowed down all encrypted file transfers for five years;

- Prohibitions on tethering: the FCC fined Verizon for charging consumers for using their phone as a mobile hotspot

- Overreaching clauses in ISP terms of service, such as prohibitions on sharing your home Wi-Fi network;

- Hindering innovation with “fast lane” discrimination that allows wireless customers without data plans to access certain sites but not the whole Internet;

- Hijacking and interference with DNS, search engines, HTTP transmission, and other basic Internet functionality to inject ads and raise revenue from affiliate marketing schemes, from companies like Paxfire, FairEagle, and others.

cases [35] “Verizon Blocks Messages of Abortion Rights Group” By ADAM LIPTAK; The New York Times; September 27, 2007

Saying it had the right to block “controversial or unsavory” text messages, Verizon Wireless has rejected a request from Naral Pro-Choice America, the abortion rights group, to make Verizon’s mobile network available for a text-message program.

…

But legal experts said private companies like Verizon probably have the legal right to decide which messages to carry. The laws that forbid common carriers from interfering with voice transmissions on ordinary phone lines do not apply to text messages.

The dispute over the Naral messages is a skirmish in the larger battle over the question of “net neutrality” — whether carriers or Internet service providers should have a voice in the content they provide to customers.

delivered a petition [22] “One Million Strong: Free Press-Led Coalition Tells FCC to Restore Net Neutrality” by Josh Levy; Freepress; January 30, 2014

warned that such an act [23] “Powell On NCTA’s 2014 Priorities: ‘Broadband, Broadband and Broadband’” By Jeff Baumgartner; Multichannel News; Oct 22 2013

If rule makers try to regulate broadband services as common carrier services under Title II of the Communications Act of 1934, “that’s World War III,” Powell said.

Chairman Tom Wheeler has said [24] “Statement by FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler on the FCC’s Open Internet Rules” – FCC; FEBRUARY 19, 2014

will pursue new [25] “FCC Plans to Allow Online Discrimination” By Brendan Sasso; The National Journal; February 19, 2014

FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler announced Wednesday he will draft new net-neutrality regulations in the wake of last month’s federal Appeals Court decision striking down the agency’s old rules. But to survive more court challenges, the new rules will likely have to be weaker than the old regime.

The old rules, adopted in 2010 by Wheeler’s predecessor, Julius Genachowski, barred Internet providers from blocking or unreasonably discriminating against websites.

The agency hasn’t written the new rules yet, but Wheeler said he plans to provide additional legal rationale to ensure that no website is “unfairly” blocked.

He said he still wants to fulfill the “goals” of the nondiscrimination rule, but he provided little detail on how he could do that without running afoul of last month’s court ruling. The FCC chairman said he plans to develop a “legal standard” and evaluate alleged violations on a “case-by-case basis.” The commission will single-out particular business practices that it would view with automatic skepticism.

The FCC official said that, based on the court’s ruling, the agency will have to allow a “two-sided market.” There is currently a one-sided market—customers pay their Internet providers to reach websites. A two-sided market would mean that websites will have to also begin paying providers to reach Internet users.

“There are going to be opportunities for individual negotiation,” the official said. “Allowing some differentiation, that’s right. But how much—that’s the big question.”

The court ruling did uphold a broad FCC authority to encourage the deployment of broadband and to promote competition.

The FCC will use that authority to prohibit certain forms of discrimination. For example, if a broadband provider like Comcast slowed down online video sites to try to pressure customers to pay for cable television, the FCC would likely still have authority to intervene to promote competition.

But a blanket prohibition on Internet discrimination appears impossible under the agency’s proposal.

some Democrats favor [26] “New Senate, House bills would restore Net neutrality” by Marguerite Reardon; C net; February 3, 2014

Several Democrats have instead been pushing for reforms to the Communications Act that would incorporate language to protect the open Internet.

face a stonewall [27] “Long-Shot Net-Neutrality Bill Introduced” By Brendan Sasso; The National Journal; February 3, 2014

The legislation has no Republican support. All Senate Republicans and all but two House Republicans voted to repeal the FCC’s net-neutrality rules in 2011.

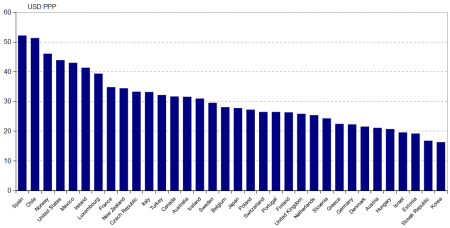

high prices, low speeds [28] OECD Broadband Portal – Prices

Figure 7.8 OECD Fixed Broadband bucket Low 2: 6 GB, 2.5 Mbit/s and above, Sept 2012. I believe this graph shows the USA as the 4th most expensive for 2.5 Mbps broadband among the 34 countries in the survey.

plans to control [29] “Verizon’s Plan to Break the Internet” by Timothy Karr; Save the Internet; September 18, 2013

In response to Judge Laurence Silberman’s line of questioning about whether Verizon should be able to block any website or service that doesn’t pay the company’s proposed tolls, Walker said: “I think we should be able to; in the world I’m positing, you would be able to.”

local government build [30] “Community Network Map” – Community Broadband Networks

Our map includes nearly 400 communities:

- 89 communities with a publicly owned FTTH network reaching most or all of the community.

- 74 communities with a publicly owned cable network reaching most or all of the community.

- Over 180 communities with some publicly owned fiber service available to parts of the community.

- Over 40 communities in 13 states with a publicly owned network offering at least 1 Gigabit services.

Such publicly owned networks [31] “Community Broadband Kicks Comcast to the Curb” by Josh Levy; Freepress; May 17, 2012

“Broadband at the Speed of Light” is an in-depth case study of how three communities — Bristol, Va., Chattanooga, Tenn., and Lafayette, La.— built next-generation broadband networks that deliver a faster, more affordable Internet than their corporate competitors.

much more speed [32] “Broadband at the Speed of Light” by Christopher Mitchell; The Institute for Local Self-Reliance; 9 Apr 2012

The new report offers in-depth case studies of BVU Authority’s OptiNet in Bristol, Virginia; EPB Fiber in Chattanooga, Tennessee; and LUS Fiber in Lafayette, Louisiana. Each network was built and is operated by a public power utility.

Mitchell believes these networks are all the more important given the slow pace of investment from major carriers. According to Mitchell, “As AT&T and Verizon have ended the expansion of U-Verse and FiOS respectively, communities that need better networks for economic development should consider how they can invest in themselves.”

* * *

By Quinn Hungeski, [36]TheParagraph.com [37], Copyright [36] (CC BY-ND) [38] 2014