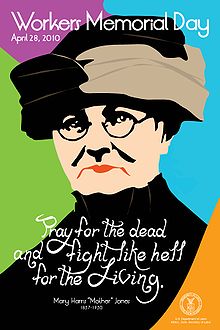

Mary Harris “Mother” Jones fought to bring a decent life to American workers’ families. In this pursuit she traveled the country, North and South, East and West. In 1903, the United Mine Workers’ (UMW) executive board asked her to check on the conditions of coal miners in Colorado. In her autobiography, Mother Jones told how she went undercover:1

I … got myself an old calico dress, a sunbonnet, some pins and needles, elastic and tape and such sundries, and went down to the southern coal fields of the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company.

As a peddler, I went through the various coal camps, eating in the homes of the miners, staying all night with their families. I found the conditions under which they lived deplorable. They were in practical slavery to the company, who owned their houses, owned all the land, so that if a miner did own a house he must vacate whenever it pleased the land owners. They were paid in scrip instead of money so that they could not go away if dissatisfied. They must buy at company stores and at company prices. The coal they mined was weighed by an agent of the company and the miners could not have a check weighman to see that full credit was given them. The schools, the churches, the roads belonged to the Company. I felt, after listening to their stories, after witnessing their long patience that the time was ripe for revolt against such brutal conditions.

In November 1903, many hard metal miners in Colorado were already on strike.2 And the mining companies’ man, the Republican James Peabody, had won the governorship in the last election, when the Democratic and Populist candidates split the progressive vote. Gov. Peabody promised to make Colorado “safe for investments”, and backed a corporate vigilante campaign to wipe out the hard metal miners’ union, the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). That campaign marked what came to be known as the “Colorado Labor Wars.” In this atmosphere, on November 9th, the Colorado coal miners struck. But a few weeks later the mine operators of the northern coal fields yielded, and UMW headquarters called a convention in Louisville to end the strike in those northern fields. Mother Jones went to Louisville to stop that action, and the miners called on her to speak:

“Brothers,” I said, “You English speaking miners of the northern fields promised your southern brothers, seventy per cent of whom do not speak English, that you would support them to the end. Now you are asked to betray them, to make a separate settlement. You have a common enemy and it is your duty to fight to a finish. The enemy seeks to conquer by dividing your ranks, by making distinctions between North and South, between American and foreign. You are all miners, fighting a common cause, a common master. The iron heel feels the same to all flesh. Hunger and suffering and the cause of your children bind more closely than a common tongue. I am accused of helping the Western Federation of Miners, as if that were a crime, by one of the National board members. I plead guilty. I know no East or West, North nor South when it comes to my class fighting the battle for justice. If it is my fortune to live to see the industrial chain broken from every workingman’s child in America, and if then there is one black child in Africa in bondage, there shall I go.”

The delegates rose en masse to cheer. The vote was taken. The majority decided to stand by the southern miners, refusing to obey the national President.

UMW president John Mitchell kept trying to get the miners of the northern fields to go back to work, and succeeded at last, when he threatened to cut off their support. Though she felt that the strike in the southern fields would now be lost, Mother Jones stayed there to fight for it. But Gov. Peabody wrote an order banishing her from the state, and sent members of the militia to take her to La Junta to take the next train out of Colorado. But Mother Jones, with thanks to a sympathetic railroad engineer, instead took the next train in to Denver:

In Denver I got a room and rested a while. I sat down and wrote a letter to the governor, the obedient little boy of the coal companies.

“Mr. Governor, you notified your dogs of war to put me out of the state. They complied with your instructions. I hold in my hand a letter that was handed to me by one of them, which says ‘under no circumstances return to this state.’ I wish to notify you, governor, that you don’t own the state. When it was admitted to the sisterhood of states, my fathers gave me a share of stock in it; and that is all they gave to you. The civil courts are open. If I break a law of state or nation it is the duty of the civil courts to deal with me. That is why my forefathers established those courts to keep dictators and tyrants such as you from interfering with civilians. I am right here in the capital, after being out nine or ten hours, four or five blocks from your office. I want to ask you, governor, what in Hell are you going to do about it?”

I called a messenger and sent it up to the governor’s office. He read it and a reporter. who was present in the office at the time told me his face grew red.

“What shall I do?” he said to the reporter. He was used to acting under orders. “Leave her alone,” counseled the reporter. “There is no more patriotic citizen in America.”

Mother Jones described the scene around Cripple Creek, Colorado, the center of the hard metal strike:

All civil law had broken down in the Cripple Creek strike. The militia under Colonel Verdeckberg said, “We are under orders only from God and Governor Peabody.” Judge Advocate McClelland when accused of violating the constitution said, “To hell with the constitution!” There was a complete breakdown of all civil law. Habeas corpus proceedings were suspended. Free speech and assembly were forbidden. People spoke in whispers as in the days of the inquisition. Soldiers committed outrages. Strikers were arrested for vagrancy and worked in chain gangs on the street under brutal soldiers. Men, women and tiny children were packed in the Bullpen at Cripple Creek. Miners were shot dead as they slept. They were ridden from the country, their families knowing not where they had gone, or whether they lived.

When the strike started in Cripple Creek, the civil law was operating, but the governor, a banker, and in complete sympathy with the Rockefeller interests, sent the militia. They threw the officers out of office. Sheriff Robinison had a rope thrown at his feet and [was] told that if he did not resign, the rope would be about his neck.

Three men were brought into Judge Seeds’ court — miners. There was no charge lodged against them. He ordered them released but the soldiers who with drawn bayonets had attended the hearing, immediately rearrested them and took them back to jail.

Four hundred men were taken from their homes. Seventy-six of these were placed on a train, escorted to Kansas, dumped out on a prairie and told never to come back, except to meet death.

In the heat of June, in Victor, 1600 men were arrested and put in the Armory Hall. Bullpens were established and anyone be he miner, or a woman or a child that incurred the displeasure of the great coal interests, or the militia, were thrown into these horrible stockades.

Shop keepers were forbidden to sell to miners. Priests and ministers were intimidated, fearing to give them consolation. The miners opened their own stores to feed the women and children. The soldiers and hoodlums broke into the stores, looted them, broke open the safes, destroyed the scales, ripped open the sacks of flour and sugar, dumped them on the floor and poured kerosene oil over everything. The beef and meat was poisoned by the militia. Goods were stolen. The miners were without redress, for the militia was immune.

And why were these things done? Because a group of men had demanded an eight hour day, a check weighman and the abolition of the scrip system that kept them in serfdom to the mighty coal barons. That was all. Just that miners had refused to labor under these conditions. Just because miners wanted a better chance for their children, more of the sunlight, more freedom. And for this they suffered one whole year and for this they died.

Coal miners in Carbon County in Utah had also joined the strike, and Mother Jones went there to cheer them.3 There too the state militia came for Mother Jones, and quarantined her inside a tiny room on the pretense that she had been exposed to smallpox. But people would still come to talk with her:

One Saturday night I got tipped off by the postoffice master that the militia were going to raid the little tent colony in the early morning. I called the miners to me and asked them if they had guns. Sure, they had guns. They were western men, men of the mountains. I told them to go bury them between the boulders; deputies were coming to take them away from them. I did not tell them that there was to be a raid for I did not want any bloodshed. Better to submit to arrest.

Between 4:30 and 5 o’clock in the morning I heard the tramp of feet on the road. I looked out of my smallpox window and saw about forty-five deputies. They descended upon the sleeping tent colony, dragged the miners out of their beds. They did not allow them to put on their clothing. The miners begged to be allowed to put on their clothes, for at that early hour the mountain range is the coldest. Shaking with cold, followed by the shrieks and wails of their wives and children, beaten along the road by guns, they were driven like cattle to Helper. In the evening they were packed in a box car and run down to Price, the county seat and put in jail.

Not one law had these miners broken. The pitiful screams of the women and children would have penetrated Heaven. Their tears melted the heart of the Mother of Sorrows. Their crime was that they had struck against the power of gold.

Two days after the raid, a company-hired goon burst in on Mother Jones:

[T]he stone that held my door was suddenly pushed in. A fellow jumped into the room, stuck a gun under my jaw and told me to tell him where he could get $3,000 of the miners’ money or he would blow out my brains.

“Don’t waste your powder,” I said. “You write the miners up in Indianapolis. Write Mitchell. He’s got money now.”

“I don’t want any of your damn talk,” he replied, then asked: “Hasn’t the president got money?”

“You got him in jail.”

“Haven’t you got any money?”

“Sure “ I put my hand in my pocket, took out fifty cents and turned the pocket inside out.

“Is that all you got?”

“Sure, and I’m not going to give it to you, for I want it to get a jag on to boil the Helen Gould smallpox out of my system so I will not inoculate the whole nation when I get out of here.”

“How are you going to get out of here if you haven’t money when they turn you loose?”

“The railway men will take me anywhere.”

There were two other deputies outside. They kept hollering for him to come out. “She ain’t got any money,” they kept insisting. Finally he was convinced that I had nothing.

This man, I afterward found out, had been a bank robber, but had been sworn in as deputy to crush the miners’ union. He was later killed while robbing the post office in Price. Yet he was the sort of man who was hired by the moneyed interests to crush the hopes and aspirations of the fathers and mothers and even the children of the workers.

From these strikes, Mother Jones drew lessons about unity among workers, and lawlessness among corporate and government elders:

The strike in the southern fields dragged on and on. But from the moment the southern miners had been deserted by their northern brothers, I felt their strike was doomed. Bravely did those miners fight before giving in to the old peonage. The military had no regard for human life. They were sanctified cannibals. Is it any wonder that we have murders and holdups when the youth of the land is trained by the great industrialists to a belief in force; when they see that the possession of money puts one above law?

Sources

1. ‘The Autobiography of Mother Jones’ Chapter XIII

2. ‘Colorado Labor Wars’ — Wikipedia’

3. ‘The United Mine Wokers of America’ by Allan Kent Powell

A strike began in Colorado began in September 1903, and within a matter of days coal miners in Utah’s Carbon County joined the strike when they were recruited by UMWA organizers sent from Colorado.

***

By Quinn Hungeski – Posted at TheParagraph.com

Can’t tell you how wonderful it is to read this history of Mother Jones. Thank you.

Came here on the recommendation of Mike Malloy just now on the radio. Will be back.

Always glad for a truth-seeker to drop by.

Would anyone know where I could purchase the 2010 poster of Mother Jones?