The Speed-Up

“I wanted a union not so much for the money,” said line worker Peter Schmitz, “I wanted a union … to have a little say so about the speed of that line. Like I say you couldn’t do quality work, it just wasn’t possible that you could do quality work the way you had to work2 [3].” In the 1930’s Schmitz worked at a General Motors (GM) automobile factory in Flint, Michigan. During the Great Depression, GM, the largest industrial corporation in the world, made the most money in the world1 [4]. In 1936, it netted $225 million – 24% of capitalization. Its top executives made 200 times the money of its average worker, who made far below the federal decency standard for a family of four. But it was the speed-up that pushed many to the breaking point. “The men worked like fiends,” said one witness, “their jaws set and eyes on fire. Nothing in the world exists for them except the line chassis bearing down on them relentlessly.”

Strike On

“What do we do about the dies?”, asked the union leader Robert Travis1 [4]. During lunch hour, night shift, December 30, 1936, a red light had summoned the workers of the GM Fisher Body plant 1 in Flint to the union hall across the street. A worker answered, “Well them’s our jobs. We want them left right here in Flint.” Travis reviewed the situation: two days earlier the Cleveland Fisher Body workers had started a sit-down strike, and that night the Flint workers saw dies being loaded onto railroad cars, clearly to move production to a plant with a weaker union. Travis asked again, “What do we do?” “Shut her down! Shut the goddamn plant!”, cried the workers. “[The men] made a race for the plant gates, running in every direction towards the quarter-mile-long buildings,” reported the union editor, Henry Kraus, who was at the meeting. Some ran to the railroad dock where the cars loaded with dies were being coupled. “Strike on,” they yelled to the engineer. He nodded and said “Okay,” signalled the brakeman to stop work and trotted off.

Buick Body Barricades

The workers hauled unfinished Buick bodies to each entrance to form barricades1 [4]. They welded steel frames around each door, and covered each window with a bullet-proof metal sheet that had a hole cut for a fire hose nozzle. The workers elected committees for running the strike: food, police, information, sanitation and health, safety, “kangaroo court,” entertainment, education and athletics. The union hall served as the hub of the outside support operation, which formed committees for food preparation, publicity, welfare and relief, pickets and defense, and a chiseling committee to collect food and supplies, going door to door. Two hundred people, mostly women, prepared food for feeding several thousand workers, both inside and outside the plants (Fisher 2 was also struck). Hundreds of workers gave use of their cars to the union. A nursery at the union hall took care of children while their mothers were working for the strike. Pickets worked the front of the plant around the clock.

Sitting Down The Detroit News

Solid for the Union

“This whole block of stores is solid for the union,” said a local drugstore owner1 [4]. “Hell, I never got anything out of GM dividends: a union victory is better for my business.” On Cadillac Square in downtown Detroit 150,000 rallied in support of the strikers4 [5]. Food and money flowed in from all across the country. Workers at Hudson and Chrysler started a one-hour-a-day club, giving one hour’s wages each day to the strike fund.

Rally on Cadillac Square The Detroit News

James Stoolpigeon

“We had a Black Legion in this town made up of stool pigeons and little bigotty kind of people,” recalled Bob Stinson, who served as a messenger and scavenger during the sit-downs5 [6], “on the same order as the Klan, night riders. Once in a while, a guy’d come in with a black eye. You’d say, ‘What happened?’ He’d say, ‘I was walking along the street and a guy come from behind and knocked me down.’ The Black Legion later developed into the Flint Alliance. It was supposed to be made up of the good solid citizens who were terrorized by these outside agitators, who had come in here to take over the plant. They would get schoolkids to sign these cards, housewives. Every shoe salesman downtown would sign these cards. Businessmen would have everyone in the family sign these cards. They contended they had the overwhelming majority of the people of Flint.” Also, foremen at non-struck GM plants pressured workers to sign Flint Alliance membership cards, but most of the cards came back with names like “John Fink” and “James Stoolpigeon1 [4]“.

The Battle of Bulls Run

“The minute the cops opened that door [the workers] rushed right out at em, everyone of them fightin’ or at least they were swingin’ their hands,” recalled sit-downer Roscoe Rich about the police’s attempt to run the strikers out of Fisher 22 [3]. “Well these [cops] had gas masks on and … the [workers would] grab the gas mask and tear it off, they’d hit him in the jaw …” “The police was trying to get in as we got the fire hoses out and turned the hoses on ‘em, where they couldn’t get into the shop,” recalled sit-downer Robert Mamero. “I was up on the second floor and they were shooting tear gas through the windows and I went over on top of the paint shop. … we had hinges and bolts and everything else [for] throwing at the police. … I got shot here in the leg and I got shot in the hip.” One female picketer, Genora Johnson, went to the sound truck and called to the police through the loudspeakers, “Cowards! Cowards! Shooting into the bellies of unarmed men and firing at the mothers of children6 [7].” A hush came over the watching crowd to hear a woman’s voice coming out of all the turmoil3 [8]. “Women of Flint! This is your fight! Break through those police lines and come down here and stand beside your husbands and your brothers and your uncles and your sweethearts.” Genora Johnson recalled what happened next6 [7]:

“In the dusk, I could barely see one woman struggling to come forward. A cop had grabbed her by the back of her coat. She just pulled out of that coat and started walking down to the battle zone. As soon as that happened there were other women and men who followed. The police wouldn’t shoot people in the back as they were coming down, so that was the end of the battle. When those spectators came into the center of the battle and the police retreated, there was a big roar of victory. That battle became known as the Battle of Bulls Run because we made the cops run.”

The next day, Governor Frank Murphy sent in the National Guard.

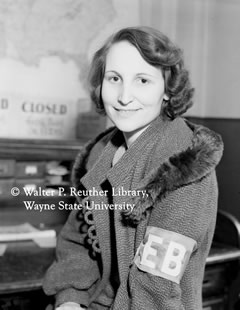

Genora Johnson Walter Reuther Library

The Women’s Emergency Brigade

“It can’t be somebody who’s weak of heart,” said Genora Johnson to the Women’s Auxiliary, after asking who would join the Emergency Brigade6 [7]. “You can’t go hysterical if your sister beside you drops down in a pool of blood.” She recalled what happened next:

“One old woman in her early seventies stood up. I said, ‘This is going to be too difficult for you.’ She said, ‘You can’t keep me out. My sons work in that factory. My husband worked in that factory before he died and I have grandsons in there.’ She went on and gave a speech. She got applause, then she walked over and signed her name. Then a young girl, I think she was sixteen or seventeen, stood up and said, ‘My father works in that factory. My brothers work in that factory. I’ve got a right to join, too.’ She walked over and signed, and all the women applauded. We recruited about 400 women for the Brigade out of about 1,000 women in the Women’s Auxiliary.”

The Women’s Emergency Brigade

Truce and Double-Cross

Governor Murphy brokered a truce: the sit-downers would leave the plants, and GM would bargain solely with the United Auto Workers (UAW), keeping the plants closed till an agreement was reached1 [4]. The workers, though disappointed at not getting outright union recognition, cleaned-up, packed-up and stood ready to leave. Meanwhile, a United Press reporter handed Henry Kraus a press release that he had picked up from the desk of the head of the Flint Alliance, and asked for comment. The release, to be published the next day, said that GM would meet with the Flint Alliance to discuss recognition – a violation of the truce. Travis sent runners to the plants to halt the workers’ exit so they could discuss the matter. The workers chose to stay, and when word got to the thousands outside they cheered and applauded wildly. Days passed, and GM sought a court order to oust the sit-downers.

A Greasy Piece of Paper, a Candle-Lit Room

The Chevy 4 plant made all the Chevrolet engines – one million a year1 [4]. It was the biggest of the nine Chevy plants spread around the Flint River. One night Genora Johnson’s husband, Kermit, came home from his job at Chevy 4 with a greasy piece of paper. “You know, I’ve figured out how we can take Plant 4,” he said, then pointed at the paper6 [7]. “Plant 8 is located here. Plant 6 is there. If we pull a strike, we’ll have workers from all these other plants march into Plant 4. The problem is that General Motors has recruited professional Pinkertons, plant protection and organized vigilantes. It will be one big slaughter unless we distract them from that area and give ourselves time to barricade the plant.”

On January 31st, after a Sunday night meeting of Chevrolet workers, Travis kept 150 stewards and organizers over. One by one they entered a room lit only by a single candle to meet with Travis, Kraus and another leader, Roy Reuther. Most left with a slip of paper holding an instruction: “Follow the man who takes the lead.” But the leaders picked 30 and gave them a more specific plan: the next afternoon at 3:20 the union would begin a sit-down at Chevy 9. After that Travis took the two most trusted leaders from Chevy 9 and told them that Chevy 6 was the real target, so they only needed to hold out until 6 was taken. Only three plant leaders from Chevy 6 and Chevy 4, including Kermit Johnson, got the whole, real plan: the leader from 6 would rally the men to go to 4 to help the other two in taking that huge plant. Among the group of 30 were a few stool pigeons, who duly reported to Chevy 4’s superintendent, Arnold Lenz, that Chevy 9 would be struck.

Chevy Plants The Detroit News

The Capture of Chevy 4

The next afternoon, in the personnel building next to the Chevy 9 plant, the entire armed force of the Chevrolet division waited1 [4]. When the night shift marched in yelling “Strike!”, the guards rushed them, with Lenz leading the charge shouting “Reds! Communists!”. The outnumbered workers fought with anything they could grab against the guards’ clubs and gas guns. The women of the Emergency Brigade heard a window break6 [7]. “We saw the head of Tom Klasey look out,” recalled Genora Johnson. “Blood was streaming down his face and he was yelling, ‘They’re gassing us in here! For God’s sake, they’re gassing us!’ That’s all we had to hear. We used our clubs to smash the windows out so the men inside could get some air.” Meanwhile, the plant manager at Chevy 4 tapped the pro-company men to help at Chevy 9, leaving 4 with virtually no pro-company muscle1 [4]. After a half hour of fighting, the two leaders at Chevy 9, figured they had held long enough and surrendered, ordering their men to march out. Meanwhile, union men at Chevy 4 stopped the conveyors, rallied the workers to join the strike, and placed barricades. The guards returning from the Chevy 9 battle tried to enter the northeast gate, but the workers, wielding pistons, connecting rods, rocker arm rods and fire hoses, drove them off. Hundreds of women of the Emergency Brigade came and locked arms in front of the gates to form a human shield against attack.

Smashing Windows to Let Out Tear Gas Walter Reuther Library

Crowd at Chevy 9(?) UPI / The Bettmann Archive

Forces Gather

The next day, February 2nd, the National Guard cleared the area around Chevy 4 and sealed off the plant1 [4]. A judge had ordered the Fisher sit-downers out, and as the zero hour approached, forces gathered on both sides. The police deputized hundreds, many from the Flint Alliance10 [9]. Thousands of workers streamed into Flint from area factories, joining thousands of Flint citizens around the Fisher plants. The Emergency Brigade rallied thousands of women, who marched from downtown Flint to Fisher 1, where they joined the throng in a huge picket line, six abreast, circling the plant in both directions. The workers inside wired Murphy: “… Governor, we have decided to stay in the plant. We have no illusions about the sacrifices which this decision will entail. We fully expect that if a violent effort is made to oust us many of us will be killed and we take this means of making it known to our wives, to our children, to the people of the state of Michigan and the country, that if this result follows from the attempt to eject us, you are the one who must be held responsible for our deaths!” Inside Fisher 1 most of the sit-downers signed up for the fight-to-the-death committee, which would fight attackers floor-by-floor right up to the roof. Days passed, more deputies signed-up, GM re-entered negotiations, and the governor did not order the Guard to move against the strikers.

Union Victory

On February 11th, the 44th day of the sit-down, GM signed a contract with the UAW recognizing it as the sole bargaining agent for the struck plants and for the UAW members in the other plants1 [4]. “One found himself wondering what home life would be like again,” wrote one sit-downer. “Nothing that happened before the strike began seemed to register in the mind any more. It is as if time itself started with this strike. What will it be like to go home and to come back tomorrow with motors running and the long-silenced machines roaring again? But that is for the future …” One by one the struck plants emptied to great cheering and a swelling parade. Kraus described the exit of the Chevy 4 sit-downers: “Lungs that were already spent with cheering found new strength as the brave men whose brilliant coup had turned the strike to definite victory began to descend the stairs.” He said that the cheering as Fisher 2 emptied “exceeded all bounds of hearing.” Thousands sang ‘Solidarity Forever’ [10] as the mass of people flowed downtown.

The Golden Age

After a century of bloody strikes7 [11], the tide had turned for American workers. Right after the Flint union victory, a wave of sit-down strikes swept the country1 [4]. Wages rose and UAW membership reached 300,000 within a few months. A month after the victory, the largest steel corporation, U.S. Steel, signed a contract with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) – without a strike. The CIO organized five million workers in about four years. Shortly after the victory, the Supreme Court affirmed workers’ rights to join unions that could bargain for them. The next year Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which established the standard 40 hour work week with time-and-a-half for overtime. By 1947, more than one third of U.S. workers belonged to a union8 [12], and the golden age had dawned for American manufacturing and the American middle class9 [13].

Sources

1 [14] ‘How Industrial Unionism Was Won: THE GREAT FLINT SIT–DOWN STRIKE AGAINST GM 1936-37′ by Walter Linder [15]

2 [16] ‘The Flint Sit-Down Strike Audio Gallery, Transcript Browser’ – MSU [17]

4 [20] ‘The historic 1936-37 Flint auto plant strikes’ By Vivian M. Baulch and Patricia Zacharias, The Detroit News [21]

5 [22] ‘Hard Times’ by Studs Terkel, pp. 156-7 [23]

6 [24] Striking Flint: Genora (Johnson) Dollinger Remembers the 1936-37 General Motors Sit-Down Strike … as told to Susan Rosenthal [25]

7 [26] ‘Timeline of Labor Issues and Events’ – Wikipedia [27]

8 [28] ‘McKinley or Roosevelt? This Election is as Much About the Past as the Future’ by Thom Hartmann [29]

9 [30] ‘Screwed: The Undeclared War Against the Middle Class and What We Can Do About It, excerpt’ by Thom Hartmann [31]

Roosevelt’s programs worked. His economic stimulus programs put money in the pockets of the people, and their purchases created consumer demand, which led entrepreneurs to start businesses to meet that demand, which meant they had to hire workers, who were well paid because 35 percent of America was unionized. Those well-paid workers bought more goods, creating more demand, and America became the world’s strongest economy through most of the twentieth century. The New Deal ushered in what has been called the Golden Age of the middle class, from 1940 to 1980.

10 [32] ‘Flint Faces Civil War’ By Charles R. Walker, Feb. 8, 1937, The Nation [33]

* * *

By Quinn Hungeski [34] – Posted at G.N.N. [35] & TheParagraph.com [36]